Oct 10, 2019

“You may tend to remember predictions you made that worked out well but forget those that did not.” From Serious About Retiring, Temuna Press, 2019, p. 167

Predicting is easy. Being right is hard.

When something bad happens in your health, do you assume that your new situation is the new normal? Or do you think that the situation will get even worse? Or are you likely to feel that things will go back to normal?

Your answers to these questions will have a profound effect on how you think about and plan for your future years in retirement. For example, problems with pain or mobility might encourage you to think shorter-term than necessary and thereby miss much of the positive impact of a longer life.

Through the years as I age, I have seen the full range of outcomes in my own health. I am frequently surprised. Sometimes pains, such as in knees or hips or other places, develop. I am convinced that it is the beginning of the end. But it isn’t. They go away. Maybe they will return or maybe not. On the other hand, small things can get big and must be dealt with immediately.

There is an adage attributed in part to Cicero in 45 BC and also to the lesser-known playwrights Norton and Sackville in 1561. It is: “Hope for the best, but plan for the worst.” I think that there is more to it than that. The adage should also include “and do what you can.”

Here are some ideas on what you can do to manage your future health. They will not happen on their own – you need to make them happen.

- Improve your diet and exercise programs. Stop harmful behaviors (e.g. drugs, smoking, excessive pain killers and alcohol.)

- Monitor your health frequently, perhaps quarterly, to identify problems before they get big and hard to fix. This could include measuring metabolites at least annually.

- Work closely – actively and regularly – with your physician and other professionals on your health. You can use Google to help you formulate the questions to ask, but the Internet is not a substitute for the substantial skills and practical experience that professionals have in diagnosis and treatment.

- Get recommendations and referrals from your physicians to others that can help diagnose problems and improve your general health.

- Make sure that you have accountability partners to keep you on track and facilitate change.

Even with all of these you will have health challenges. There are no guarantees, except that you will eventually die. Even so, a commitment to managing your health now may lessen the chances of premature bad outcomes and could improve the quantity and quality of your future life.

Sep 26, 2019

Jim and Kate are moved by many charitable appeals. They give a variety of small contributions throughout the year. They have thought about giving more but are held back by two major concerns. First, they do not want to run out of retirement money themselves and become dependent on their children or social welfare programs. Second, they want to give the bulk of their inheritance to their children who could really use it.

Waiting to give charity until death has the advantage of giving the money when you no longer need it. The disadvantage of waiting is missing out on the joy of giving. Many people do some of both.

The choice between children and charity is to some extent a false choice. Consider some of the details of Jim and Kate’s situation.

Jim and Kate have two children and an estate worth approximately $500,000 – half investments and half equity in their home. They would really, really like some of their money to go to solve world hunger issues, particularly to benefit children. They have identified the charity that most closely matches their objectives.

Jim and Kate ask themselves the question, “What if our children were to inherit $200,000 each instead of their full share of $250,000? Would the $50,000 difference materially affect their lives?” They conclude that the $50,000 would not make much difference to the children. Jim and Kate realize that they have just effectively found $50,000 X 2 = $100,000 to benefit world hunger upon their deaths.

By far the most common approach to contributing to charity is to write a check or use a credit card to pay. However, there is an alternative approach that may have some tax advantages.

If your IRA permits it, you can set up a checkbook that draws against it. If you use those IRA checks to pay bills, they are deemed to be IRA withdrawals, fully taxed, and possibly subject to penalties and fees. But if those checks instead go to standard (501c3) charities, they are not. You can effectively use pre-tax dollars for your charitable giving.

Furthermore, if you are age 70½ or greater and taking your Required Minimum Distributions, then such charitable checks count towards your RMD. You have thereby reduced the rest of your RMD owed and saved some taxes.

You can use a comparable approach to making charitable contributions upon your death. If your estate contains both retirement and personally held investments, it matters which assets go to your children and which to charity. If the retirement money through its beneficiary goes to your family, it is taxed; if it goes to charity, it is not. So to some extent, the charitable contribution pays for itself through a reduction in taxes.

You should integrate this approach to charitable giving with your other planning. See a professional for details.

The author does not provide tax, legal or accounting advice. This material has been prepared for informational purposes only and is not intended to provide, and should not be relied on for tax, legal or accounting advice. You should consult your own tax, legal, accounting and financial advisors before engaging in any transaction or taking any actions regarding the content discussed above.

If you have comments or questions, contact me at Mark@SeriousAboutRetiring.com

Sep 4, 2019

Sometimes I meet people who are stressed out about their investments. They are concerned about possible imminent declines in their investment values or even future returns not living up to past performance. The lurking fear is that they will not have enough money to accomplish what they want to in their retirement. The risks they face may be substantial. The stakes are high, and the dangers are real.

Retirement can heighten the risks you have. Investments that have fallen in value may not have time to recover before you need the money. You may be more dependent on investment income because you no longer have paid work.

Here are three important tools you can use to address your concerns.

Get educated and take a long-term perspective. Newspapers and other media work hard to sell their services. Frightening, even alarming, news tends to sell. Acting on short term advice can too easily lead to getting whipsawed – selling low and buying high. Reacting to current events in this way can be expensive in time and money.

To put things in perspective, find out the research – what has really happened in the past. For example, the media have recently been sounding the alarm about the “inverted yield curve,” when short-term interest rates are higher than long-term rates. Yes, the research says that an inverted curve has frequently preceeded economic downturns. But a sour economy does not necessarily cause stock prices to fall. Thus, the yield curve might or might not be an issue for investors.

Where can you get good research to gain perspective? Not from marketers but from researchers who publish in peer-reviewed academic journals and professional advisors who are familiar with the research.

Concentrate on actions, not outcomes. You may be particularly concerned about how things will turn out. And you may not be able to control the outcomes of what is happening. However, you may still be able to take action. Concentrate on planning for and managing evolving situations. Prepare and get help as needed.

Talk things out. Talking can you give you both emotional and practical support. If you talk with an expert, you can get practical ideas that you can put to good use.

There are certainly no guarantees that situations will develop as you want them to. But preparation and management will help you in two ways. First, your actions may well lead to better outcomes. Second, you will feel more in control of your life, which in and of itself will build self-confidence and more constructive actions.

Aug 20, 2019

The following is an excerpt from my book Serious About Retiring, Temuna Press, 2019. It is available at Amazon.

There are many reasons why now, as you plan for retirement, may be the right time to review and perhaps make changes to your estate planning.

- You may originally have done your estate planning long ago.

- Your family, health, and/or work circumstances may have changed.

- You may have very different ideas about how you want your estate handled after your death.

- You now likely have a realistic attitude toward mortality and an acceptance of the fact that “you can’t take it with you.”

- You may have witnessed the results of successful or unsuccessful estate planning for your parents or other relatives or friends.

- If you have successfully managed your money so far and continue to do so during retirement, you may well have a considerable amount to pass on. A larger estate may be the result of

- the growth of your savings and investments over time,

- an inheritance,

- funds remaining in an emergency buffer built up to deal with, say, healthcare expenses, and

- your house, if you still have one.

A challenge in working on your estate plan is deciding how best to distribute the funds. What if you have more than one offspring and their circumstances are quite different from one another? For example, one child or grandchild might have serious health problems and future expenses but not the other children. Do you give more to the individual who needs it the most? Or what if one child is far more financially successful than the others? Do you give that one less? Or if you have already made substantial monetary gifts to one child, do you give more in your estate to the others to make up for the share they missed? Or what if you like one child less than the others? Do you arrange to leave him or her less of your estate or even nothing at all?

Answers to each of these questions have financial ramifications as well as psychological ones. Is an equal distribution the same as a fair one? There is no single right answer to any of these questions, and you may well have different ideas from others you know. You must decide what is right for you. As the circumstances for you and your beneficiaries evolve, you can imagine working quite closely and productively with your estate planning attorney.

The author does not provide tax, legal or accounting advice. This material has been prepared for informational purposes only and is not intended to provide, and should not be relied on for tax, legal or accounting advice. You should consult your own tax, legal, accounting and financial advisors before engaging in any transaction or taking any actions regarding the content discussed above.

If you have comments or questions, contact me at Mark@SeriousAboutRetiring.com

Aug 7, 2019

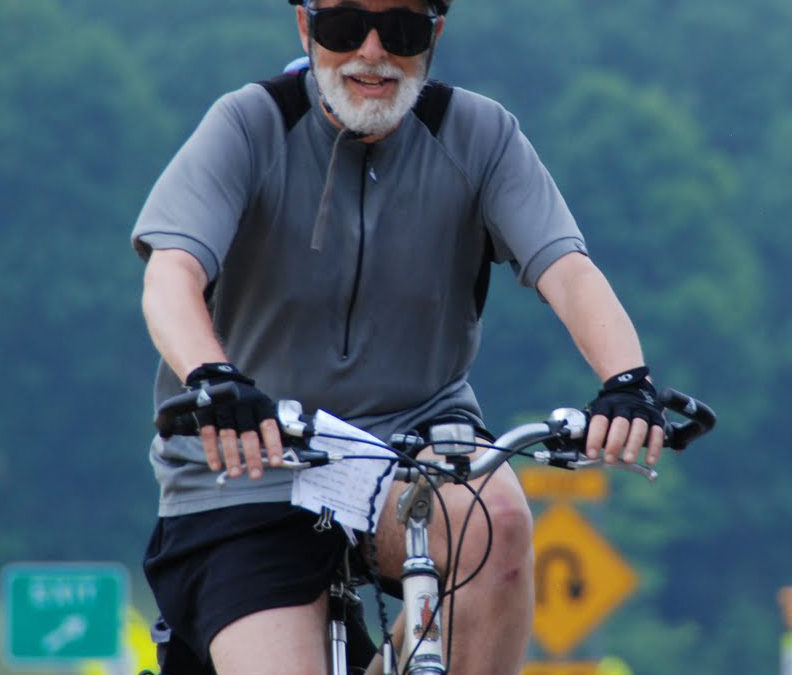

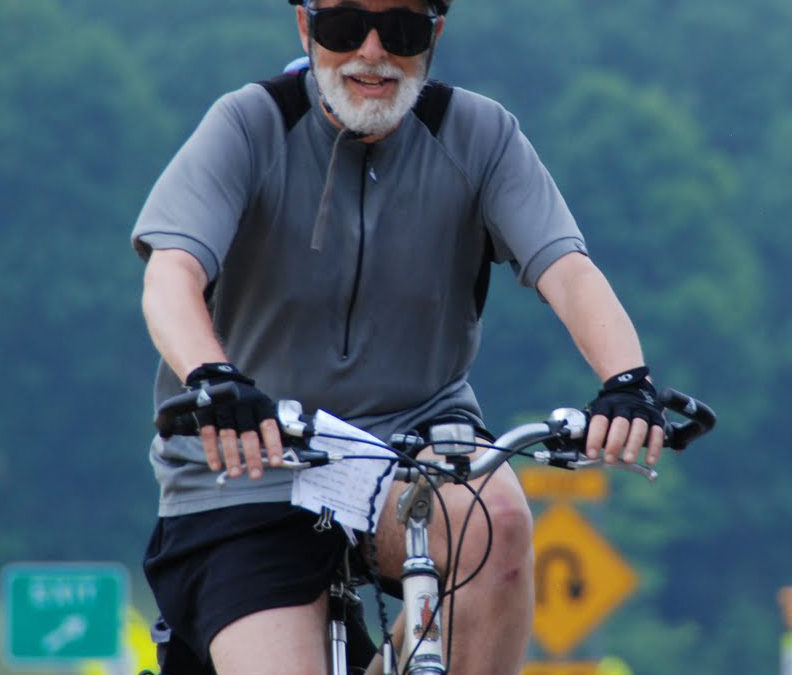

Everyone has their own unique retirement journey. Here is mine. You may get some ideas for your own.

Work journey

I grew up in the Sputnick era and majored in Chemistry in college. My first professional job was in graduate school where I was an assistant in a chemistry lab and did research. Over nearly 25 years I had many achievements, including a PhD degree from UC Berkeley under the supervision of a Nobel laureate, a fellowship in the Medical School at UW Madison, a biochemistry teaching job at UMass at Amherst, many federal research grants and publications, and working in the computer area for a number of years.

Retirement Chapter 1

Investing was my hobby from the age of 8 – it was a father-son shared activity. In my early 40’s I turned my hobby and passion into my profession. This was very exciting for me, the fulfillment of a dream that I at first did not realize was a possibility. I had flexibility with my time and was able to take many vacations each year. I felt almost like I was retired!

This new career was easy and enjoyable, although there was much to learn. My job contained many firsts – learning about insurance and planning in addition to investments, hiring my first employee who eventually became my business partner, meeting and helping many interesting people, and running my own business. My first ten years were at The Equitable (now called AXA).

Retirement Chapter 2

After ten years, I launched an independent financial planning practice. Four years later, while on vacation, I had a heart attack that nearly killed me. I reflected on why I had not died. I realized that my financial planning work was much more than a job. It was my calling – to use my God-given talents to improve the lives of others.

Over the next 14 years I built up my business. I was working but I also was spending my time on my hobby—so I might have been retired.

Retirement Chapter 3

At age 68 I decided to retire (again?), at least partly, by cutting back on my work load. Another advisor offered to take over most of my business and provide service to the rest of my clients. I retained only a fifth of my previous clients, and the other advisor provided substantial support to me as I worked with him.

Surely I was retired then. Or partly retired. In celebration of my newly available non-work time I embarked on a few conventional retirement activities:

- I joined a bike club for seniors—we do 20 bike-mile trips on Wednesday mornings.

- I wrote a book— Serious About Retiring.

- I started taking cello lessons.

Retirement Chapter 4

At the end of this year I will be retiring fully from my financial planning practice. I will continue my activities of biking, writing, and playing cello. But I also have other activities in mind.

My wife Lucy Rose is a gerontologist, artist and writer. Her fifth book on aging, Grow Old With Me, comes out in September. We plan to speak together on aging topics starting in October of this year and in coming years.

I am also gearing up to do retirement coaching for people who need help transitioning to retirement. This will be a way to continue on my calling of helping people.

Some observations on retiring

I see retirement as another life stage that offers an opportunity to increase the quality of your life. A better life means growing as a person, making more of a contribution to people around you and having an impact.

Friends ask me, Are you really retired or still working? I don’t care what you call it—I’m having an exciting and fulfilling life.

I wish the same for you. I would love to get your comments and answer your questions about your own journey. Contact me at Mark@SeriousAboutRetiring.com

Jul 23, 2019

How much will your future lifestyle cost? Will your Social Security and investment income be enough to pay for the lifestyle you want?

If that’s not enough, you could have up to six other possible, less common, sources of income.

Two of the potential income sources would be available only if arranged long before retirement:

- You could work for one of the 5% of American companies that provides pensions. Right now these include Johnson & Johnson, Coca Cola, JPMorgan Chase, Merck and Prudential. In addition, schools and governments frequently offer pensions. Some employers will also provide a continuation of health benefits upon retirement. In any case, you should check all of your previous employers to verify what you are entitled to.

- You might accumulate property or develop products that will produce a regular income when you retire. You can purchase and develop commercial, residential or other properties to rent out in retirement. You might write a book or software or invent something. All of these could generate royalties—but only if successful and profitable.

To generate more income after retirement you could:

- Work part-time for pay. Part-time might be seasonal or some parts of the day, week or month. The work might be in the same company as pre-retirement or different companies. Job responsibilities could be the same or quite different from what they were before retirement.

- Sell something of value that you own. It could be a boat or vacation home. Or you could downsize your home. You would then invest the cash proceeds to generate supplemental income.

- Apply for financial aid if you qualify for it. Governments, charities and religious institutions are the largest providers. Government programs include Medicaid and food stamps. The most common financial aid for seniors is Medicaid to pay for long-term care, but each state has strict rules on income eligibility. These programs are generally available only for people with exceptionally low incomes and, in fact, only fifteen percent of seniors use Medicaid.

- Get help from family or friends. The most common providers of such aid in retirement are children or siblings. Sometimes the help is in-kind, e.g. room or board. Sometimes parents might provide support, if still alive, or thorough an inheritance upon death.

All six of these sources of extra income take planning, and some may not be feasible or desirable for you.

As described in previous blogs, your income from Social Security could be maximized by using an effective claiming strategy. Of course, the more you save and invest over your working years, the more money you will have as your retirement investment income. During retirement, you also can maximize income through your selection of investments and your strategy for distributing income while taking income taxes into account.